Crisp air, the hustle and bustle of harvest, bonfires, football, and pumpkin spice everything—all remind us of the beauty of fall. Unfortunately, the season also brings back the all-too-familiar hack of influenza in pigs. Effectively managing influenza not only protects herd health but also helps secure the long-term productivity of the farm.

Understanding Influenza in Pigs

Influenza is a virus that circulates commonly in all stages of pigs in the Midwest and throughout the world. Pipestone’s approach is to eliminate influenza where possible at the source, which is often the sow farm. Vaccinating sows can eliminate influenza circulation in growing gilts and in the farrowing house. Unfortunately, there is no highly effective vaccine to protect growing pigs from becoming infected.

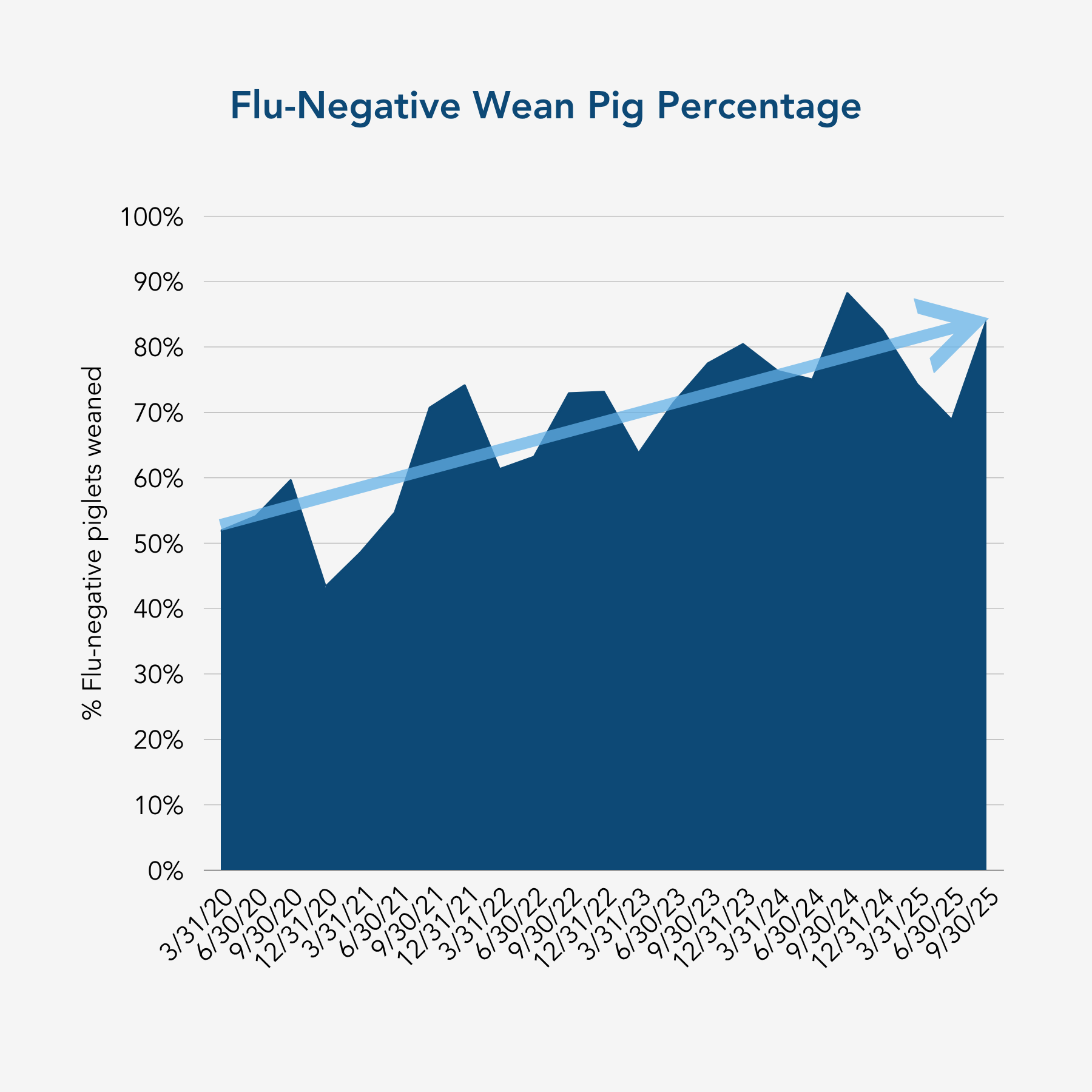

Pipestone continues to be a leader, pushing for influenza elimination, both for managed sow farms and for the industry. Since our initial efforts for better influenza control about seven years ago, we have made significant progress in weaning more negative pigs to shareholders. Still, there is work to be done.

Influenza is extremely common in the grow-finish phase of production. Transmission occurs through direct contact and airborne routes. Management practices such as reducing stressors and implementing all-in/all-out systems with proper cleaning and disinfection can help reduce infection risk.

Influenza presents both acutely and subclinically. Acute cases show sudden onset of coughing, fever, and nasal discharge, with lethargy being another common sign. Astute producers who monitor water consumption often pick up influenza infections 24–36 hours before clinical signs appear. In subclinical cases, respiratory signs may be less obvious. The severity of breaks and production losses is often worse with co-infections such as PRRS or Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae.

When influenza first appears, there are many common next steps. Anti-inflammatories are often used to lower fevers and improve pig activity. During illness, caretakers should enter barns more often to stir pigs and encourage them to get up, eat, and drink. While influenza is viral and does not respond to antibiotics, secondary bacterial infections are a serious and common complication in grow-finish pigs. Antibiotic treatment may be necessary to minimize production losses. Influenza damages the respiratory tract lining, making it easier for opportunistic bacteria to cause life-threatening pneumonia. As a result, caretakers often need to increase the number of individual injectable treatments. In larger outbreaks, producers often deliver medications (anti-inflammatories and sometimes antibiotics) through the water supply. Your veterinarian is the best resource for tailoring diagnostic and treatment plans specific to your farm.

Moving From Aspirin to Meloxicam

For decades, aspirin was commonly used to help pigs manage influenza, PRRS, and other infections. That changed in fall 2024 when the FDA issued a “Dear Veterinarian” letter reminding the industry that the Animal Medicinal Drug Use Clarification Act (AMDUCA) prohibits the extra-label use of unapproved drugs in food-producing species. Because aspirin is not FDA-approved for food animals, there is no legal pathway for its use in swine. Pipestone no longer carries or recommends aspirin, and we do not expect this option to return.

As the industry adapts, Pipestone has been recommending oral meloxicam, an NSAID, as an alternative. Meloxicam is a water-soluble, prescription, non-antibiotic medication that reduces fever and encourages pigs to eat and drink during influenza infections. It is available in two sizes, mixes easily with most antibiotics, and producers can administer it for several consecutive days under veterinary direction. Though more expensive than aspirin, meloxicam remains a practical and effective water medication with a 17-day withdrawal period.

Colder temperatures often bring influenza back to the barn. Meloxicam has become a practical tool for managing outbreaks. Work with your Pipestone veterinarian to develop a herd-health strategy—one that strengthens your operation now and future-proofs it for the years ahead.